You are going to learn practical skills such as how to avoid strange numerical errors caused by the way that computers represent numbers.

You will learn how to optimize your C code by using clever tricks that exploit the designs of modern processors and memory systems.

You will learn how the compiler implements procedure calls and how to use this knowledge to avoid the security holes from buffer overflow vulnerabilities that plague network and Internet software.

You will learn how to recognize and avoid the nasty errors during linking that confound the average programmer.

You will learn how to write your own Unix shell, your own dynamic storage allocation package, and even your own Web browser.

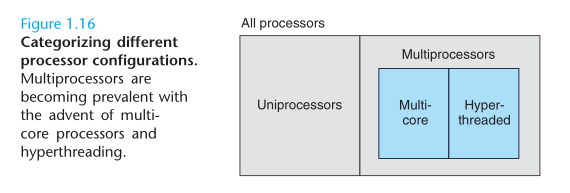

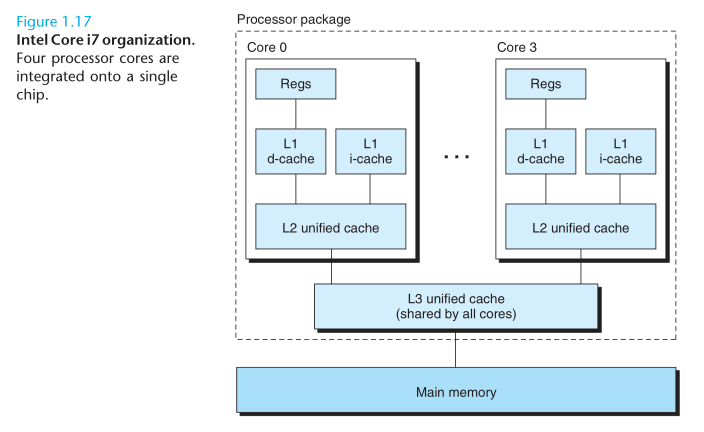

You will learn the promises and pitfalls of concurrency, a topic of increasing imprtance as multiple processor cores are integrated onto single chips.

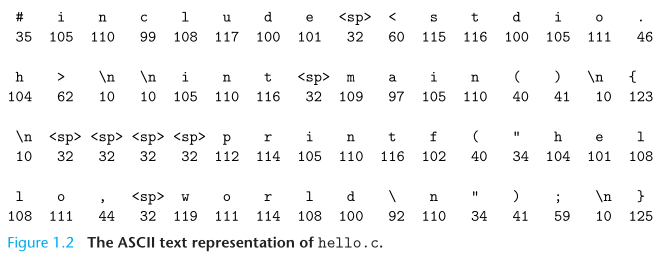

The source program is a sequence of bits, each with a value of 0 or 1, organized in 8-bit chunks called bytes. Each byte represents some text character in the program.

Most modern systems represent text characters using the ASCII standard that represents each character with a unique byte-sized integer value.

The representation of hello.c illustrates a fundamental idea: All information in a system - including disk files, programs stored in memory, user data stored in memory, and data transferred across a network - is represented as a bunch of bits. The only thing that disinguishes different data objects is the context in which we view them. For example, in different contexts, the same sequence of bytes might represent an integer, floating-point number, character string, or machine instruction.

As programmers, we nned to understand machine representations of numbers because they are not the same as integers and real numbers. They are finite approximations that can behave in unexpected ways.

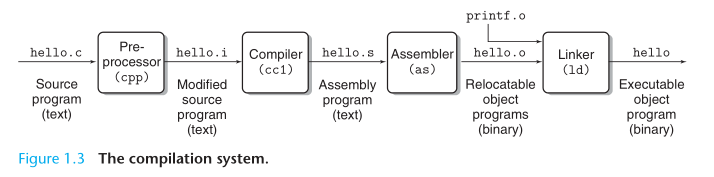

In order to run hello.c on the system, the individual C statements must be tranlated by other programs into a sequence of low-level machine-language instuctions. These instructions are then packaged in a form called an executable object program and stored as a binary disk file.

Each statement in an assembly-language program exactly describes one low-level machine-language instruction in a standard text form. Assembly language is useful because it provides a common output language for different compilers for different high-level languages. For example, C compilers and Fortran compilers both generate output files in the same assembly language.

The assembler translates hello.s into machine-language instructions, packages them in a form known as a relocatable object program, and stores the result in the object file hello.o. The hello.o file is a binary file whose bytes encode machine language instructions rather than character.

The printf function resides in a separate precompiled object file called printf.o, which must somehow be merged with our hello.o program. The linker handles this merging. The result is the hello file, which is an executable object file (or simple executable) that is ready to be loaded into memory and executed by the system.

The GNU project is a tax-exempt charity started by Richard Stallman in 1984, with the ambitious goal of developing a complete Unix-like system whose source code is unencumbered by restrictions on how it can be modified or distributed.

The are some important reasons why programmers need to understand how compilation systems work:

- Optimizing program performance.

- Understanding link-time errors.

- Avoiding security holes. A first step in learning secure programming is to understand the consequences of the way data and control information are stored on the program stack.

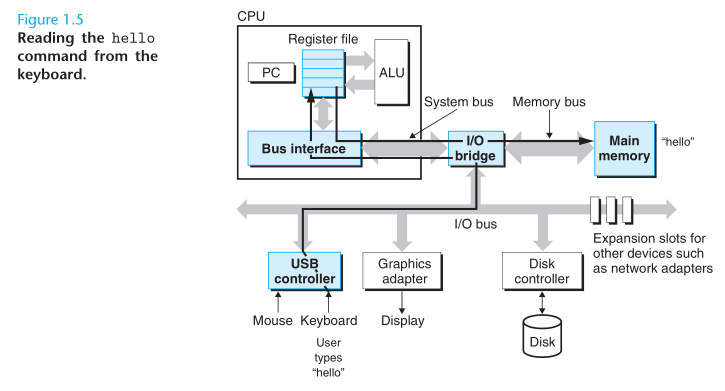

The shell is a command-line interpreter that prints a prompt, waits for you to type a command line, and then performs the command. If the first word of the command line does not correspond to a built-in shell command, then the shell assumes that it is the name of an executable file that it should load and run.

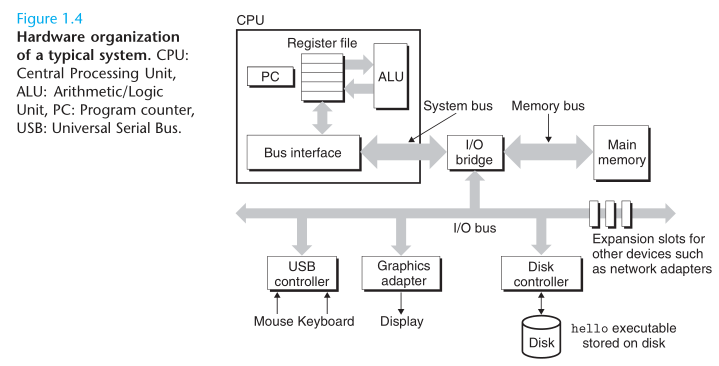

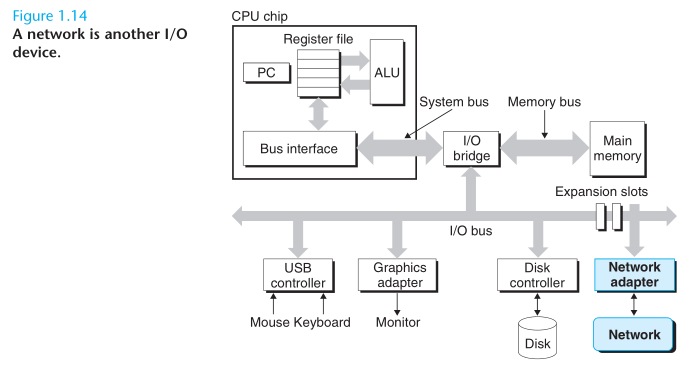

Buses

- Running throughout the system is collection of electrical conduits called buses that carry bytes of information back and forth between the components. Buses are typically designed to transfer fixed-sized chunks of bytes know as words. The number of bytes in a word (the word size) is a fundamental system parameter that varies across systems. Most machines today have word sizes of either 4 bytes (32 bits) or 8 bytes (64 bits).

I/O Devices

- Input/Output (I/O) devices are the system’s connection to the external world. Each I/O devices is connected to the I.O bus by either a controller or an adapter. Controllers are chip sets in the device itself or on the system’s main printed curcuit board (often called the motherboard). An adapter is a card that plugs into a slot on the motherboard. Regardless, the purpose of each it to transfer information back and forth between the I/O bus and an I/O device.

Main Memory

- The main memory is a temporary storage device that holds both a program and the data it manipulates while the processor is executing the program. Physically, main memory consists of a collection of dynamic random access memory (DRAM) chips. Logically, memory is organized as a linear array of bytes, each with its own unique address (array index) starting at zero.

Processor

- The central processing unit (CPU), or simple processor, is the engine that interprets (or executes) instructions stored in main memory. At its core is a word-sized storage device (or register) called the program counter (PC). At any point in time, the PC points at (contains the address of) some machine-language instruction in main memory. From the time that power is applied to the system, until the time that the power is shut off, a processor repeatedly executes the instruction pointed at by the program counter and updats the program counter to point to the next instruction. The processor reads the instruction from memory pointe at by the program counter (PC), interprets the bits in the instruction, performs some simple operation dictated by the instruction, and then updates the PC to point to the next instruction, which may or may not be contiguous in memory to the instruction that was just executed.

We say that a processor appears to be a simple implementation of its instruction set architecture, but in fact modern processors use far more complex mechanisms to speed up program execution. Thus, we can distinguish the processor’s instruction set architecture, describing the effect of each machine-code instruction, from its microarchitecture, describing how the processor is actually implemented.

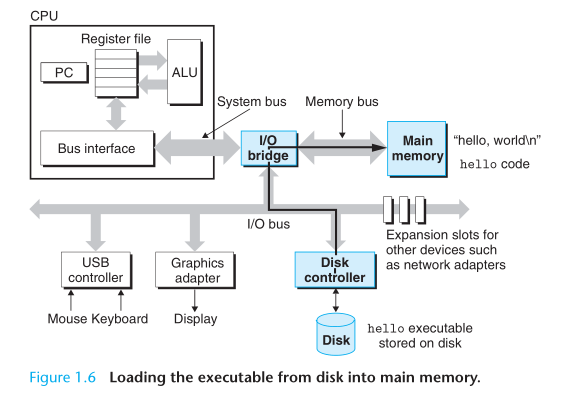

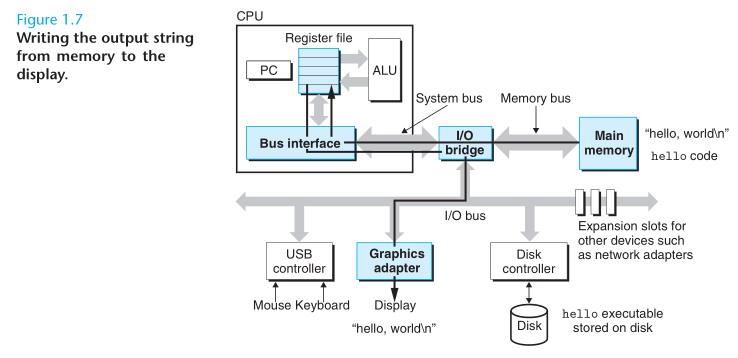

When we hit the enter key on the keyboard, the shell knows that we have finished typing the command. The shell then loads the executable hello file by executing a sequence of instructions that copies the code and data in the hello object file from disk to main memory. Using a technique knows as direct memory access (DMA), the data travels directly from disk to main memory, without passing through the processor.

An important lesson from this simple example is that a system spends a lot of time moving information from one place to another (disk, main memory, processor, display device, etc). From a programmer’s perspective, much of this copying is overhead that slows down the “real work” of the program. Thus, a major goal for system designers is to make these copy operations as fast as possible.

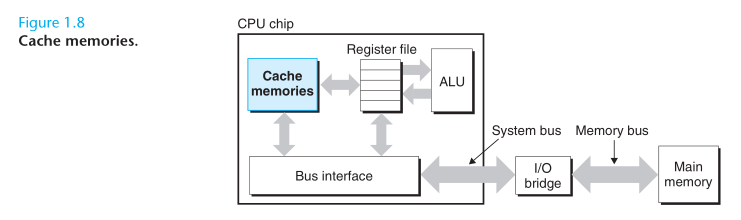

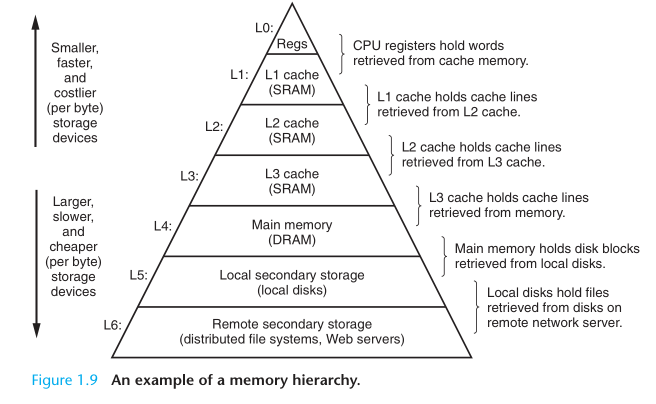

To deal with the processor-memory gap, system disigners include smaller faster storage devices called cache memories that serve as temporary staging areas for information that the processor is likely to need in the near future.

The L1 and Le caches are implemented with a hardware technology known as static random access memory (SRAM). The idea behind caching is that a system can get the effect of both a very large memory and a very fast one by exploiting locality, the tendency for programs to access data and code in localized regions.

One of the most important lessons in the book is that application programers who are aware of cache memories can exploit them to improve the performance of their programs by an order of magnitude.

The main idea of a memory hierarchy is that storage at one level serves as a cache for storage at the next lower level. On some networked systems with distributed file systems, the local disk serves as a cache for data stored on the disks of other systems.

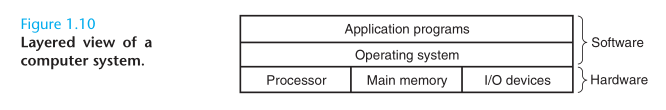

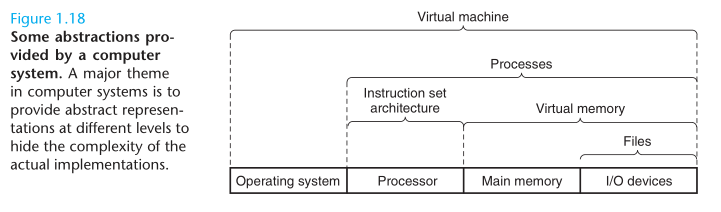

We can think of the operating system as a layer of software interposed between the application program and the hardware.

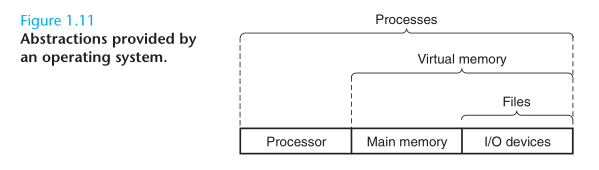

The operating system has two primary purposes: (1) to protect the hardware from misuse by runaway applications, and (2) to provide applications with simple and uniform mechanisms for manipulating complicated and often wildly different low-level hardware devices. The operating system achieves both goals via the fundamental abstractions show in Figure 1.11: processes, virtual memory, files. As this figure suggests, files are abstractions for I/O devices, virtual memory is an abstraction for both the main memory and disk I/O devices, and processes are abstractions for the processor, main memory, and I/O devices.

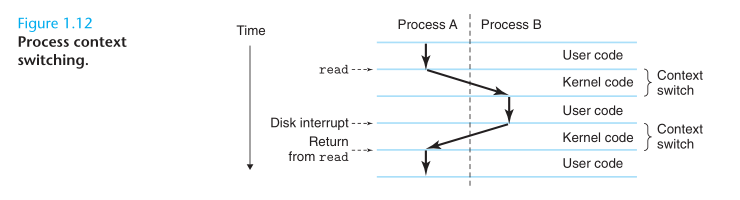

A process is the operating system’s abstraction for a running program. Multiple processescan run concurrently on the same system, and each process appears to have exclusive use of the hardware. By concurrently, we mean that the instructions of one process are interleaved with the instructions of another process. The operating system performs this interleaving with a mechanism known as context switching. The operating system keeps track of all the state information that the process needs in order to run. This state, which is known as the context, includes information such as the current values of the PC, the register file, and the contents of main memory.

Although we normally think of a process as having a single control flow, in modern systems a process can actually consist of multiple executing units, called thread, each running in the context of the process and sharing the same code and global data.

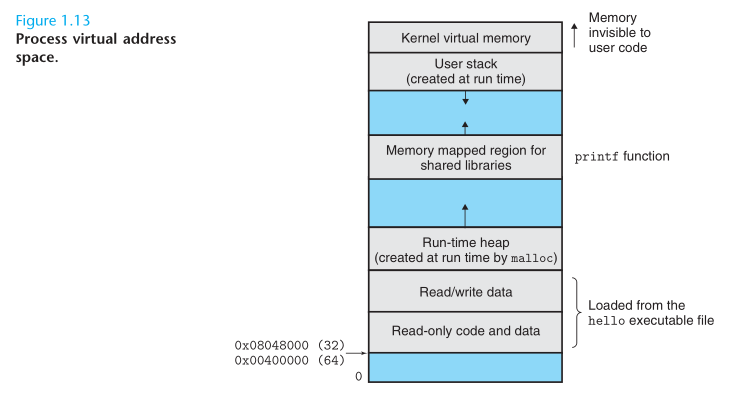

Virtual memory is an abstraction that provides each process with the illusion that it has exclusive use of the main memory, Each process has the same uniform view of memory, which is known as its virtual address space.

The virtual address space seen by each process consists of a number of well-defined areas, each with a specific purpose.

- Program code and data.

- Heap.

- Shared libraries.

- Stack.

- Kernel virtual memory.

A file is a sequence of bytes, nothing more and nothing less. Every I/O device, including disks, keyboards, displays, and even networks, is modeled as a file. All input and output in the system is performed by reading and writing files, using a small set of system calls known as Unix I/O. This simple and elegant notion of a file is nonetheless very powerful because it provides applications with a uniform view of all of the varied I/O devices that might be contained in the system.

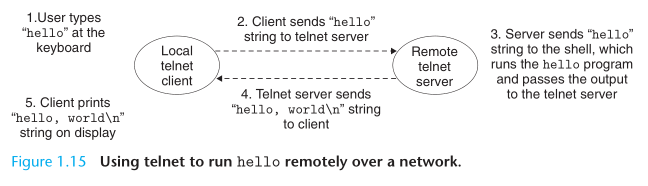

From the point of view of an individual system, the network can be viewed as just another I/O device.

We use the term concurrency(并发) to refer to the general concept of a system with multiple, simultaneous activities, and the term parallelism(并行) to refer to the use of concurrency to make a system run faster. Parallelism can be exploited at multiple levels of a abstraction in a computer system. We highlight three levels here, working from the highest to the lowest level in the system hierarchy.

- Thread-level concurrency

- Instruction-level parallelism

- Single-Instruction, Multiple-Data (SIMD) parallelism

At a much lower level of abstraction, modern processors can execute multiple instructions at one time, a property known as instruction-level parallelism.

At the lowest level, many modewrn processors have special hardware that allows a single instruction to cause multiple operations to be performed in parallel, a mode known as single-instruction, multiple-data, or “SIMD” parallelism. For example, recent generations of Intel and AMD processors have instructions that can add four pairs of single-precision floating-point numbers in parallel.

The use of abstraction is one of the most important concepts in computer science. For example, one aspect of good programming practice is to formulate a simple application-program interface (API) for a set of functions that allow programmers to use the code withought having to delve into its inner workings.

On the processor side, the instruction set architecture provides an abstraction of the actual processor hardware. With this abstraction, a machine-code program behaves as if it were executed on a processor that performs just one instruction at a time. The underlying hardware is far more elaborate, executing multiple instructions in parallel, but always in a way that is consistent with the simple, sequential model. By keeping the same execution model, different processor implementations can execute the same machine code, while offering a range of cost and performance.

On the operating system side, we have introduced three abstractions: files as an abstraction of I/O, virtual memory as an abstraction of program memory, and processes as an abstraction of a running program. To these abstractions we add a new one: the virtual machine, providing an abstracion of the entire computer, including the operating system, the processor, and the programs.

Information inside the computer is represented as groups of bits that are interpreted in different ways, depending on the context.

Processors read and interpret binary instructions that are stored in main memory.

Storage devices that are higher in the hierarchy serve as caches for devices that are lower in the hierarchy.